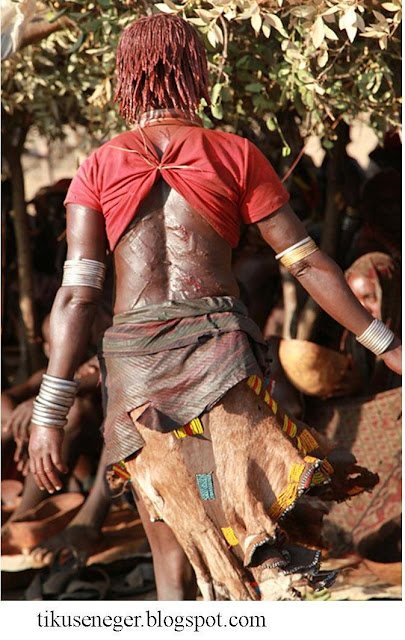

Once they reach the waiting maza, the women begin to tease and

verbally harass the men in order to provoke them. The men, who are clutching

long thin sticks, are hesitant to react at first. Finally, however, they start

to beat the women across their bare backs with the switches.

These are not playful strokes, either, but blows often strong

enough to break the sticks in half. Each swipe leaves a gash in the women’s

flesh, but still the women continue to provoke the maza to strike them again

and again.

There are two motives behind this voluntary whipping. First,

it’s a way for the women of the family to show support for the boys who are

undergoing the cattle jumping initiation. The more lashes they sustain and the

greater their injuries, the more devotion they have demonstrated for their

brothers and other male relatives. The second reason is to secure the boys’

loyalty. Now that the girls have proven their commitment, the boys are expected

to look out for them in the future, should they ever be in need of help.

The women’s scars will serve as reminders of this commitment.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the Ethiopian government is in favor of ending the

whipping part of the bull jumping ceremony. But for now, the women themselves

want to keep the practice alive.

This young man is having his face painted in preparation for the

ritual: the red paint with white spots is meant to imitate the coloring of a

leopard. Until he performs the jump, no male Hamer may marry, own cattle, or

have children, so it’s an important milestone in his life. Before making the

leap, he is rubbed down with sand to scrub away his sins and is smeared with

cow dung for strength.

Although the cattle jumping

ceremony takes place during the course of one afternoon, the festivities go on

for much longer than that. The invitations are sent out to relatives and

friends in the form of a strip of bark with knots marking off the number of

days until the initiation. Invited guests may have to travel great distances to

arrive at the site. And in preparation, they begin drinking and feasting for

days in advance.

Here, the maza hold the cattle steady. Their age varies according to

when they made their own jumps: boys from wealthier families are usually able

to perform the ritual earlier. Boys stay maza (which translates as

“accomplished one”) until they get married. And when they get married depends

on when their families can find someone suitable, or afford to pay their dowry.

Until then, the young men travel from village to village to assist with the cow

jumping rituals, for which they are paid in food and drink

Around 15 cows and castrated bulls

(representing the women and children of the tribe) are chosen for the ceremony

and lined up in a row. The place of cattle in this ritual signifies their

importance in Hamer life. For these semi-nomadic pastoralists, cattle herds are

both symbols of wealth and an essential source of food, especially in lean

times when they rely on their cows’ blood and milk to survive.

Highlighting the animals’

importance, there are 27 words in the Hamer dialect to describe the differences

in the color and texture of a cow’s coat. A Hamer man is also known by three

names: his human name, his goat name, and his cow name.

Now, the cattle have been rubbed

with dung to make them extra slippery – in case the challenge isn’t sufficient

already! On top of that, the young man being initiated must make his jumps

completely naked, except for two pieces of bark tied across his chest.

He needs to complete four

successful leaps over the animals, but if he falls he’s allowed to pick himself

up and try again. The watching crowd cheers him on with their backs to the

west, which is where they believe all evil should go.

Although this activity is called

bull jumping, getting across the backs of 15 cows and castrated bulls actually

involves a fair bit of running and balancing. Fortunately, the cattle are held

in place by the maza to lessen the likelihood of accidents.

By performing this difficult task,

the Hamer boy is moving beyond childhood into manhood. Until now, he has been

considered immature, sexually unclean, and of low worth, which is why he has

not been allowed to marry. All that will change once he completes his fourth

jump.

The boy – now a man – literally

leaps into responsible adulthood to the roars of his supporters. Yet although

this challenge may be over, more difficult ones lie ahead.

The development of Ethiopia brings

benefits and problems for tribal people like the Hamer. More and more young

people are abandoning traditional ways in favor of urban life – where they

drink stronger alcohol and sometimes find themselves falling prey to less

scrupulous people. It’s a time of transition for the Hamer people, and one that

will no doubt take many years to complete.